山 本 廣 展

YAMAMOTO

HIROSHI (雅号 大廣)

1939 福井県鯖江市生まれ

1961

東京學藝大学卒業

稲村雲洞(’52)、宇野雪村(’54)に書を学ぶ

1955 第 7回毎日書道展 第

4回奎星展(以後毎回出品)

1961 日本の書展(ナングー・ギャラリー、シアトル)

第

10回記念奎星展 上田桑鳩賞(桑鳩単独審査)

1966 個展 画廊紅(京都)

1967 個展 画廊紅(京都)

1977 第

26回奎星展 上田桑鳩記念賞

1981 MAY(武生)

1982 玄美 [ 貪] 展 玄美大賞(宇野雪村単独審査)

1984

ギャラリーZEN(鯖江)

1986 いづみ画廊(福井)

1988 毎日書道展

40周年記念「日本現代書法芸術北京展」(故宮博物院、北京)

1989 アール・ギャラリー(武生)

1990 ギャラリーZEN(鯖江)

1991

いづみ画廊(福井)

1992 いづみ画廊(福井)

「山本廣作品集」刊行(月精舎)

1994 北電「エルフ福井」ギャラリー(福井)

<文字のコスモロジー>

1995 ギャラリーG2(福井)

福井県立美術館(福井)自主企画 <3つの個 >

1996

福井県立美術館(福井)自主企画 <3つの個 >

1997 福井県立美術館(福井)自主企画 <3つの個 >

1998

福井県立美術館(福井)自主企画 <3つの個 >

マイルストン・アート・ワークス(富山)

ギャラリー17(金沢)

ギャルリーMMG(東京)<封印>

1999 ギャラリー17(金沢)

2002

ギャルリーMMG(東京)<宇宙卵>

「現代の書 新春展」(東京セントラル美術館)

2004 萬歳楽(石川県鶴来・現

白山市)<花ヲ尋ネ水ヲ尋ヌ>

2005「2005ソウル書藝ビエンナーレ」特別賞(韓国)

2006「現代の書 新春展」(東京セントラル美術館)

「2006台北国際現代書藝展(中正芸廊、台湾)

世界書藝祝祭「国際現代書藝展」(韓国)

「韓中日現代書 20人展」(物波空間画廊、ソウル)

2007

慶尚南道書藝大展「日本現代書藝作家特別招請展」(韓国 昌原市 )

2008 ソウル書藝ビエンナーレ「国際現代書展」(国立藝術の殿堂、ソウル)

ギャラリー揺(京都)<宇宙卵Ⅱ>

上上美術館国際芸術年展(北京)

「書と非書の際」ギャラリー・サロン・ドHYOUGO(パリ)

2009

MURAI・ホワイトレーベル(福井)<文字力>

「書と非書の際」(ART FORUM

JARFO まいづる智恵蔵・京都)

2010「書と非書の際」(ART FORUM JARFO まいづる智恵蔵・京都)

「第

9回国際書法交流奈良大会」(主催 毎日新聞社)

2011「書と非書の際」(ART FORUM

JARFO まいづる智恵蔵・京都)

「日本のイメージの多様性」展(米国・カンザス)

2012 個展 まなべミュージアム(鯖江)<龍的独白>

「書と非書の際」(ART FORUM

JARFO まいづる智恵蔵・京都)

「現代の書 新春展」(東京セントラル美術館)

物波創立

15周年記念「物波国際展」(物波空間画廊、ソウル)

2013「書と非書の際」(ART FORUM

JARFO まいづる智恵蔵・京都)

「日本精鋭書家

5人展」(物波空間画廊、ソウル)

「書と非書の際」 日中書画精鋭選抜展(京都文化博物館)

現在

奎星会同人会員 毎日書道会審査会員

主なコレクション

オルデンブルク市立美術館(ドイツ)

日本文化会館(ローマ)

鯖江市文化会館(福井県)

桜仙会館(福井県立科学技術高校)

鯖江 CCI美術館(福井県)

サバエ・コンストラクトビル(福井県鯖江市)

水仙ミュージアム+水仙ドーム(福井県越廼村・現

福井市)

サイモン・フレイザー大学ギャラリー(カナダ)

上野ケ原会館(福井県立鯖江高校)

学生ホール・ギャラリー [王山](福井県立鯖江高校)

鯖江市資料館(福井県)

福井新聞社(福井市)

ユタ大学美術館(アメリカ)

韓国書藝フォーラム(ソウル)

坂井市春江東小学校(福井県)

仁愛大学(福井県越前市)

群馬セキスイハイム(前橋市)

EN・(淵)

2013.2.2

91.8×90.1cm

ETU・(曰)

2013.1.31

PM2:55

91.5×91.8cm

JIMOKU・(耳目)Ⅰ

2012

69.2×69.2cm

JIMOKU・(耳目)Ⅲ

2012.9.27

35.0×68.0cm

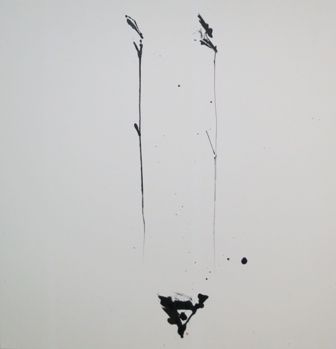

KATACHI-01209

2012

70.0×70.0cm

KI・(癸)

2013.2.1

AM11:35

91.3×91.8cm

SHU・(首)

2013.1.29

PM6:09

90.8×90.8cm

SYU・(卌)

2012

70.0×70.0cm

TAKU・(涿)

2012

60.3×59.3cm

WORK-01211a

2012

64.8×65.2cm

WORK-a

2012

32.3×29.6cm

WORK-c

2012

29.6×32.3cm

宙(そら)に-

音声

2011

89.0×89.0cm

宙(そら)に-

深呼吸

2011

89.0×89.0cm

SYU(習)

2012

90.0×87.0cm

『新たな地平へ』

―意識の先にある融通無碍と主客合一

中国の士大夫にとって書は長い間、詩や画とならぶ重要なたしなみの一つであった。文

字とともに書の意識が日本にもたらされた後にもその理解は変わることなく、身に付ける

べき教養として、日本の貴人階層に受け継がれたのである。その後、禅僧たちの精神修養

の顕現、文人たちの人格の表出、といった一面も強調され始める。近代に入ると、学校教

育との結びつきも次第に強化され、初等教育を受けた日本人であれば、筆でもって字を書

いた経験のない者などない、と断言できるまでに浸透した。そんな背景を受けて、近代に

は字を書くことを生業とする“書家”が登場してくるのである。彼らはやがてそれぞれの主

張に基づき、流派を形成して書壇という強固でギルド的なピラミッド組織を作り上げてし

まった。

このように日本の書は実に多面的な要素を持ち、現在も多くの人々が様々な立場から書

に関わっているのである。

明治の初年、そして昭和の第二次大戦以降。この二つの時期に日本は西洋の文化を大い

に取り入れた。“芸術”という概念もその一つである。もちろんそれ以前の日本にも、類す

る表現形式は存在した。遡れば縄文時代の土偶も、琳派の装飾絵画も、北大路魯山人の焼

き物といった造形物もそのスタンスの違いはあるものの、現代の日本では汎く芸術として

括られる。もちろん厳密に区分すれば、信仰に基づいた産物であり、インテリアであり、

実用を第一義とした工芸であるということもできる。日本の書はそれらのどれにも当ては

まる一面をも兼ね備えている。そこがまたやっかいなところでもあるのだ。そしてほとん

どの日本人がこの書の抱え込んだ“あいまいさ”を問題としていない。むしろ「それもまた

よろし」と受け入れている。大江健三郎がノーベル賞受賞の記念スピーチで「あいまいな

日本の私」と題して同賞受賞の川端康成が行った「美しい日本の私」のスピーチをより重

層的に捉えてみせたように。

ただ、この拙文で問題としたいのは書をめぐる日本人の育んできた独特の世界観のこと

ではない。

実は1950年代に書は欧米のアンフォルメルやアクションペインティングの作家たち

との接点があった。フランツ・クライン、デ・クーニング、ジャクソン・ポロック、マーク・

ロスコ、アルコプレー、スーラ―ジュ、アルトゥングらの作品が森田子龍の『墨美』に次々

と掲載される。日本からも海外の展覧会に森田を始め、上田桑鳩、比田井南谷、井上有一、

手島右卿、篠田桃紅らが出展した。日本の書と西洋の現代美術との蜜月時代である。積極

的な交流の中、接点の模索、または相違点を超えての啓発が試みられたが、結局袖を分か

つこととなった。

この短いが濃密であった交流をファーストコンタクトとすると、セカンドコンタクトは

いつになるのか。残念ながらその後の具体的な交流は持たれていないといえる。約半世紀

の時が流れたにもかかわらず、である。その後の書壇は大きな公募展を中心とする仕組み

の中に集約されていき、国内で自給自足できるようになってしまったせいか、戦後の溢れ

るようなエネルギーも次第に収束していったせいか、外に目を向ける必要性を個々の作家

たちが感じなくなってしまったようだ。そして平和なサンクチュアリで牧歌的な時間が過

ぎていったのである。

ところがさすがにここにきて書の分野にもさまざまな事情から金属疲労が生じ始めた。

もちろん、そんな事情とは一線を画して、純粋に自己の内なる荒野をさまよってきた者も

いる。山本廣はその中の一人である。

山本は日本の書と西洋の現代美術が接触をもった一次世代からみれば、二次世代といえ

る。醒めた知性で客観的に物事の真理を見通すことができるポジションだ。書的要素を駆

使して、欧米でいうところの“FINE

ART”(純粋芸術)のフィールドにいかに触手を伸ば

していけるかという一点に立ち位置を定め、進むべき道を見据えている。これは前世代の

経験から見ても、かなり険しく障害物や落とし穴の多い道である。ちょっと油断すると足

をすくわれかねない。そこを巧みにかいくぐって行かねばならないのだ。

例えば、文字性と造形性という観点。

当然のごとく表意文字である漢字を書けば意味が生じる。二文字連なれば言葉になる。もっ

と重なれば文学性を帯びてくる。これらは日本の書にとっては大事な要素であり、しかも

魅力的な材料だ。つい傾倒したくなる。だが、山本はこれらをことごとく寄せ付けない。「“読

まれる”

という実利的要素が大きく“見る”

という造形性に重点を置いた視覚芸術としての

位置を与えられなかった」(『山本廣作品集』月精舎 1992 以下、山本の言葉はこの

作品集に掲載されたインタビューから引用)文字性とつかず離れずの際をつま先立ちして

歩いていくようなステップ。そのあやうさに宿る魅力。「人間の精神や感性が沸沸とたぎり

ながら浄化されてかたち(文字)として湧き上がってきたもの、そこらあたりを自分の制

作の原点としたい」(山本)見えるもの、見えないものを漢字という記号に置き換えた古代

の中国。その機知と諧謔(エスプリとユーモア)。どこまでも健全であるように見えて、時

にアイロニカルな原初の造形。それはそのまま現代の造形性と幸福な結実を果たす。すべ

て書を視覚芸術たらんとするがゆえんである。

例えば線と余白という観点。

発条力をともなったさまざまな形状の筆。老子の玄之又玄にも通ずる墨の黒。紙の摩擦と

吸収が生み出す速度感、それは時間性に繋がる。「“我物一如”とういことをいいますが、自

我を超えた世界、要するにぼくの身体と筆、墨、紙、そして文字が一体となって動き息づく。

もたもたしているとそういう状態になれないんですね。ぼくのいまの仕事の特徴というの

はスピード感というか、あっという間の精神の切り取りだと思うんです。ですから速度を

もつ線としての黒と、それから現れてくる地としての白の表情も、きわめて重要な意味を

もつと考えています」(山本)

例えば精神性と叙情性という観点。

前衛書の雄である森田子龍でさえ、変遷の果てにたどり着いた境涯、「書は文字を書くこと

を場として、内のいのちの躍動が外におどり出て形を結んだものである」という言葉には

多分に禅的な匂いが漂う。井上有一の視線は少し異なるが、それでも精神主義的な呪縛か

らは逃れられていない。山本の独自性は時に度を越しかねない精神主義から距離をおくこ

とで獲得しているといえる。篠田桃紅の作には日本的叙情とよべる“わび、さび”であったり、

儚さ、うつろいやすさといった無常観が根底に漂う。熊谷守一の書は脱俗的で全人格的な

色合いがにじみ出ていて味わい深い。しかし、山本はこれらにも与しない。「(ぼくは)意

識的に叙情性を排除していて、そこが現代的だと」(山本)「淡墨による墨の色の美しさや

にじみは東洋の美の重要なものだと思いますが、そういうことに溺れると作品の本質から

遠のいてしまいます(略)現代の美術としての書の表現を真摯に求める場合、そういう余

技的、教養的要素は排除すべきだと思います」(山本)

例えば意識と無意識という観点。

ジャクソン・ポロックのドリッピング。サイ・トゥオンブリーのエクリチュール。デビュッ

フェが提唱したアール・ブリュット。正気と狂気を行ったり来たりするような。「制作とい

うのは意識と無意識のはざまの状態にあるように思いますね。ただ、墨の濃度と書くスピー

ド、筆の性能や紙質との関係は経験的に把握していますが、いったん筆が紙についた瞬間

からは、すべて空っぽ、無に近い状態になるような気がします」(山本)文字を題材としたり、

いつも決まった素材を使って制作したりするという制約は一種の足枷である。しかし野放

しの自由より、一見堅苦しくて窮屈そうな枠組みの中をかいくぐってこそ、その先に大き

な世界が広がっていることを日本の創造者たちは知っている。意識の先にある融通無碍。

円転自在の境地。そこにたどり着くために深く深く沈潜するのである。

1950年代の西洋現代美術と書の蜜月時代がよそよそしい決別に終わったことの要因

の一つに、その後の日本国内における書壇事情を挙げたが、もちろん理由はそれだけでは

ない。書の側にある根本的な問題。

― 結局、書は新たな地平を切り拓くことができなかった。

ということが、決別の大きな理由であったと考えられる。行きづまりを感じた西洋の作家

たちが書に期待したのは、西洋美術の文脈とは異なる可能性だった。しかし、書の側から

のプレゼンテーションは深化しなかった。求愛に応えられなかったのである。書展には去っ

ていた恋人に未練を示すような情念表出的な作品がはびこった。それもいつのまにか癒え

て、形骸だけが残った。くり返すが、それから半世紀。あらゆる分野でグローバル化が進む中、

新たな可能性を示さなければならない時が来ているのである。

纏わりついてきた書の因習をかいくぐり、新たな空間を創出する。視覚芸術として。東

も西もない。時間の隔たりもない普遍的な世界へ。正しいことは何か。強いということは

どういうことか。深さとはどんな尺度か。美しいとはどんな状態をいうのか。

西田幾多郎は『善の研究』の第十三章「完全なる善行」の中で述べている。

「我々の真の自己は宇宙の本体である真の自己を知れば啻(ただ)に人類一般の善と合する

ばかりでなく、宇宙の本体と融合し、神意と冥合するのである。宗教も道徳も実にここに

尽きて居る。而して真の自己を知り、神と合する法はただ主客合一の力を自得するのみで

ある」

東洋も西洋もない。縄文でもルネサンスでもない。人間として。大いなる力に繋がる仕事。

山本の創造物はその答えの一つであると確信している。

2013.1.7

ぎゃらり壺中天

服部 清人

To a New Horizon

For the versatility and the unification of subject and object beyond

consciousness

In ancient China, the elites were expected to have a knowledge of Sho (calligraphy)

as well as of poetry and painting. The Japanese, too, became aware of the

concept of Sho when the Chinese writing system was imported to Japan. Sho

was accepted among the Japanese nobility as an important part of education.

Sho also became a manifestation of Zen monks’ mental training as well as

a demonstration of integrity for Bunjin (writers and artists.) Later on

in the modern era, public schools adopted Sho as part of the curriculum,

and Sho became widespread among regular people. Anybody who received an

elementary education had a chance to write with a brush. Shoka, or professional

calligraphers, came onto the scene with this social background. Calligraphers

formed different schools based on styles and principles. This developed

into a strict guild-like hierarchy system called “Shodan”.

Japanese Sho developed with multifunctional aspects and even today many people are involved in Sho in many different ways.

Japan eagerly absorbed Western culture in the early Meiji era and also after World War II during the Showa era. The concept of Art was one of them even though Japan already had its own forms of art and had for centuries. Japanese arts such as clay figures from the ancient Jomon period, decorative paintings of Rin School, and ceramics by Kitaoji Rosanjin are all considered art today, even though they may be categorized as crafts because of their religious, decorative, or practical purposes. Japanese Sho also applies to all of the above “arts” or “crafts,” and this can make discussions of Sho complicated. Most people, however, are not bothered by the “ambiguity” of Sho, and they readily accept its ambiguity. This attitude was mentioned by Japanese novelist Oe Kenzaburo in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech entitled “Japan, the Ambiguous, and Myself.” His address took the matter even further than Japanese Novel Prize Laureate Kawabata Yasunari had in his “Japan, The Beautiful and Myself” address.

It is not my intention to discuss the unique Japanese world view around Sho with this essay.

In fact, there was an exchange between Japanese calligraphers and Western artists who were in the Art Informel and Action Painting movements of the 1950’s. Works by Franz Kline, Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Pierre Alechinsky, Pierre Soulages, and Hans Hartung were shown in Morita Shiryu’s calligraphy magazine Sumibi. Japanese calligraphers such as Morita Shiryu, Ueda Sokyu, Hidai Nangoku, Inoue Yuichi, Teshima Yukei, Shinoda Toko exhibited their works overseas. This was the honeymoon period of Japanese Sho and Western contemporary art. Both sides gave their best efforts to keep up the relationship and to develop deeper understandings in spite of their differences, but unfortunately this did not last long as they ended up going in separate ways.

This short yet deep exchange was the first interaction between Sho and Western Arts. The second interaction, however, has not happened yet even after half a century. The Japanese Sho world has established itself around some large competitions open to the public, and calligraphers did not feel a need to reach out overseas. The energetic movements seen after World War II eventually died down, too. It is a pity that the Japanese calligraphers were satisfied with their achievements within the country and allowed themselves to enjoy the idyllically calm and peaceful life in this sanctuary. This sanctuary, however, started to show various problems.

Hiroshi Yamamoto is one of the calligraphers who stayed away from this situation and chose simply to wander around in his own spiritual wilderness.

If the calligraphers who interacted with Western artists after World War II were the first generation, Yamamoto is the second generation. With his cool intelligence and an objective eye, he sees the truth. He uses the elements of Sho to reach out to “Fine Art.” He is aware of the path he must take. The experience of the first generation shows that this is a path full of obstacles and pitfalls. He should be on constant guard so that he won’t be tripped over.

Sho’s literal information and the figurative forms

Chinese characters are ideograms, so when you write a character, it naturally has a meaning. Two characters form a word. And even more characters will begin to take on literary meanings. These are such important and attractive aspects of Sho, however, we should not limit ourselves in this notion. Yamamoto does not allow himself to do so. He explains that Sho “never established a position as a form of visual art to be ‘looked at’ because of its practical role,” that of its need “to be read” (from an interview on “Works by Yamamoto Hiroshi” 1992, Gessseisha). But it also makes Sho exciting that it tiptoes around the literal information of the characters. “Characters are the crystallization of human spirit and sensitivity, and this is where I want my creative starting point to be,” says Yamamoto in his interview. Ancient Chinese expressed visible and invisible things with characters, and they did it with such great humor and wit! These early characters looked complete and wholesome, yet sometimes they showed great irony. These pure and innocent forms are linked to the aesthetics of contemporary Sho. Sho is indeed a visual art in this sense.

Sho’s lines and spaces

Various types of brushes with the energy to spring, the black of Sumi paint described as “the mystery of mysteries” by Lao‐tzu , and a sense of speed created by rubbing papers and the absorption of Sumi all lead to the concept of time. Yamamoto says, “As described by the Buddhist idea of Gabutsu-ichi-nyo (oneness of ego and non-ego), that is to say, the world beyond my ego, in other words my body, my brush, Sumi, paper, and the characters are all united and start breathing with a movement. You have to act quickly or this will not happen. My work is distinctive in its speed. It is a quick act of cutting out a part of my spirit. The black of the accelerating lines and the expression of the white that appears in the background both have very important meanings to me.

Sho’s spirituality and lyricism

Even Morita Shiryu, one of the major avant-garde calligraphers, went through many changes till he somehow reached this Zen statement: “Sho is the realization of its inner spirit in full play while using the characters as its stage.” Inoue Yuichi’s view is a little different, but he is also bound by idealism and spirituality. What makes Yamamoto unique is how he stays away from such idealism which can occasionally appear to go overboard.

Japanese aesthetics such as wabi sabi and the concept of mujo (transience) like fragility and volatility are found in the works of Shinoda Toko. Kumaya Morikazu’s unworldly Sho is profound while showing his integrity. Yamamoto is unlike either of them as he intentionally excludes lyricism from his work in order to stay modern. He believes that “the beautiful colors and the smudges of Usuzumi (light Sumi ink) are an important part of Asian art; however, you should not be overly captivated by them or they will take you away from the essence of the works …. If you sincerely seek Sho as an expression of contemporary art, you should eliminate the merely avocational and educational elements.”

Sho’s consciousness and unconsciousness

Jackson Pollock’s Dripping , Cy Twombly’s Ecriture(calligraphic style paintings,) Dubuffet’s Art Brut(raw art) all go back and forth between sanity and insanity. Yamamoto says, “When you are creating, you are right in between being conscious and unconscious. While you are aware of the density of Sumi, speed of the strokes, performance of the brush, and their effects on papers from your past experiences, at the moment you put your brush down on the paper, you enter the world of emptiness and are close to the state of Mu (nothingness).” Using characters as the subject matter and always using the same materials can be restrictions, but Japanese artists know they can reach the larger world only by going through these tight constraints. Artists reach deeper and deeper to get to the state of versatility in order to be able to express themselves readily and eloquently.

I mentioned earlier how the honeymoon period of Western Art and Sho in the 1950’s did not last long because of the various situations surrounding Japanese Sho at that time. There is, however, another reason for the unfortunate ending, and it is the primary one. It was the fundamental problem of Sho itself. Japanese Sho failed to open up a new horizon. The Western artists who felt the limitation of their arts were looking for new possibilities in Sho. Sho, however, could not respond to their passionate requests. Sho could not present anything deep enough. Hence, Sho exhibitions became full of works of emotional expression as if they were longing for Western arts, as if they were their lost lovers. Those emotions eventually faded and there remained merely a matter of formality. It has been half a century since then. Everything is going global now. I want to emphasize the need for Sho to demonstrate new possibilities. We must rid ourselves from an old convention and create a new stage. As a visual art, there is no East or West. We should go into the timeless universal world. What is right? What is being strong? How deep is deep? What is beauty?

Japanese philosopher Nishida Kitaro wrote in his book An Inquiry into the Good, “Our true self is the ultimate reality of the universe, and if we know the true self we not only unite with the good of humankind in general but also fuse with the essence of the universe and unite with the will of God-- and in this religion and morality are culminated. The method through which we can know the true self and fuse with God is our self-attainment of the power of the union of subject and object” (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 145).

There should be no distinction between East and West, or the Jomon and the Renaissance. We are all humans, and art should lead us to the great power, as Yamamoto’s does. I believe his work is work of universal and timeless artistic value.

2013.1.7

Gallery Kochuten

Hattori Kiyoto

H25年3月30日 壷中天mu-joで開かれたシンポジュウムの写真です

トップページに戻る